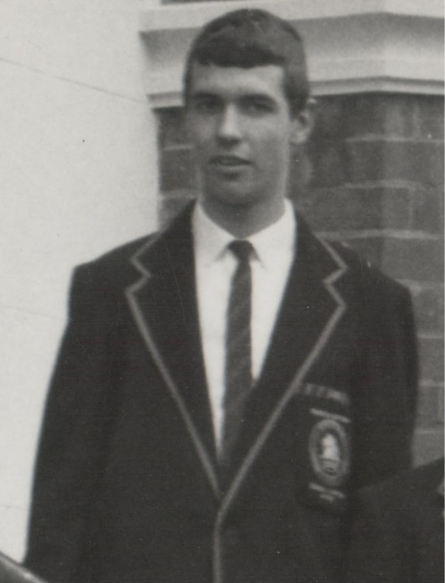

Leslie Adrian “Les” Rowe, B.A.(Hons)., Dip.Ed.

3 March 1945 – 28 February 2022

MHS 1959-1962

The following article was published in The Old Unicorn, Issue 249, Spring 2005

Trouble seems to follow Les Rowe, recently retired Australian diplomat and school captain 1962. After initial training in Canberra, his first posting was to the Australian High Commission in Ghana which covered ten countries in West Africa.

He regards this as having been a wonderful experience which enabled him to learn the job of being a diplomat and to experience a range of very different cultures.

“It was a different Africa then,” remembers Les, “AIDS had not begun its tragic march through the region, government standards were better than now. It was safe. “That having been said, a week or two after I got to Ghana there was a military coup which took place during the absence of the country’s prime minister.

“Many years later, in May 1998, I was posted to Indonesia. I arrived on the Sunday and the following Thursday, Soeharto fell. “I did warn my colleagues when I arrived in Russia. However, president Putin is still there,” he remarked wryly.”

Les went to Hughesdale state school, Lloyd Street central then MHS. His parents were Sydney and Phyllis Rowe and sister Jennifer who went to Mac.Rob. “When I was very young I remember my father pointing out MHS as we passed by in the train and saying, ‘That’s the school you’re going to.’

“He had been educated at Perth Modern, the Western Australian equivalent of MHS and was a great believer in education.”

Speaking of MHS Les observed, “The quality of education was of a very high standard thanks to the contribution of a large number of outstanding individuals. “People who had a very direct influence on my life and to whom I owe a real debt of gratitude include Ben Munday, Graeme Worrall, Neville Drohan, David Niven and Brian Corless but in singling out these few I am doing an injustice to the many others whose contribution added to the sense of quality and achievement that the school engendered in those days.

“My matric subjects were British and modern history, economics, Latin and English but in addition to the curriculum the greatness of the school lay in the fact that the teachers viewed it as their responsibility to open students’ horizons and to broaden their life experiences through a wide range of extra curricular activities and by encouraging open and free debate. “My interest in the theatre, debating and music were nurtured at this time.”

Les was in the athletic team during the four years he was at MHS. He was u15 athletics champion. He also played tennis and was in the school debating team with Gareth Evans and Russell Lansbury. He remembers having a very minor role in the school play of 1960 The Importance of Being Earnest. “Some 15 years later I was at dinner in Melbourne with some pretty sophisticated individuals and the discussion turned to that play and one of the guests said, ‘You’re not going to believe this but the most enjoyable production I ever saw of The Importance of Being Earnest was a schoolboy production at Melbourne High School.'”

He continued to be involved in theatre at Melbourne university and produced plays in Pentridge prison for the Council of Adult Education for a year or so after he graduated.

Les left Melbourne university with a BA (Hons) and Dip Ed. He taught for a year at Northcote technical school before being conscripted into the army. He spent his first year in the army undergoing training in Australia before being posted as an education instructor to the army base at Lae, Papua New Guinea. “I had a student teaching scholarship to go through university so I was obligated to teach for 3 years afterwards,” says Les.

“As it turned out, I did my year at Northcote and the national service discharged my obligation to complete the remaining 2 years. “When I was going through school I had been interested in being a teacher but I had also developed an interest in becoming a diplomat.

“My grandparents were English and travelled back and forth and I think this must have unleashed some early longings to travel and see the world. “There were also other members of the family who had lived in New Guinea and Indonesia for lengthy periods and I was always fascinated by their tales. “In addition, a lot of my school friends were the children of central European immigrants. “This helped to kindle a sense that there was a different exciting world outside to discover.

“When I was in my mid teens, a contact of my father who was in foreign affairs wrote me a long letter about a career in the foreign service and advising how to go about joining. “Although I wrote back to him I lost his letter and forgot his name. “My father died before I could refresh my memory. It was a matter of great frustration to me that I never knowingly met him or thanked him personally even though we may have worked together.”

Les started travelling at university. At the end of first year, he hitchhiked with Alex Wodak, another MHS boy, to Brisbane then caught a plane to Papua-New Guinea and travelled around for 6-8 weeks. “It was a stunning experience,” remembers Les.

“After my Dip Ed, I bought a car with a group of friends from uni and drove up to Darwin then flew to Baucau in Portuguese Timor. “We caught a small plane to Dili, went across Timor into Indonesian Timor then hitched a lift in an airforce jet ending up having christmas dinner 1967 in Bali. “The only hotel there was the Bali Beach. It was about 3 storeys high. You couldn’t even land jets at the airport, then. Kuta was just a fishing village. “But it was the most magical place and despite all, it still retains vestiges of that magic.”

In 1970 in his second year in PNG, Les applied to join the department of foreign affairs and was selected to join the intake of 1971 after a very competitive process. “I put in an application and didn’t hear anything. So I wrote again and they suggested I apply again, which I did and I still heard nothing. “I rang up from PNG while in the last year of army 1970, and they said ‘Gosh, don’t know what’s happened. Didn’t you get the request to go to Brisbane?’ I didn’t. “They rang back and suggested I come to Canberra the following week. “I managed to get the army to release me for the trip to Canberra. “When I walked in, everyone else had already had a go at the process. I did psych and other tests on the first day. “After, sitting by the fire, we were all chatting. Everyone said where they were from, Sydney, Melbourne and so on, I said Papua-New Guinea and they all said they must really want you, bringing you in from there.

“I didn’t elaborate, after all you don’t give a mug a second chance! “We then did a couple of days of seminars, interviews and written work, finished off with a cocktail party to ensure you didn’t disgrace yourself too badly. “In December I got word I had been selected. But by then I’d also put in an application to the ABC to work on PM, the radio news program. “Just before new year’s eve, I received a telegram saying, ‘Please proceed to Adelaide to take a position as a trainee television producer.’ “I was confronted with a very difficult choice. “TV and radio had always interested me, so I would’ve been happy there if I hadn’t been selected as a trainee diplomat”.

Les drove to Canberra in 1971 and started training. In September he came down to Point Cook for 3 months language training, in French because of its importance in those days as an international language. “Along the way I also picked up a working knowledge of Portuguese, can read Italian and carry out some basic conversation in Indonesian and Russian.” After 2 years in Ghana, Les returned to Canberra in January 1973.

“In the foreign service you soon learn that, however important you might think you are when you’re serving abroad, Canberra is the centre of the world for us,” says Les. “It’s where the business of government is done and it’s where policy is developed. “It’s very much the case, now even more than then, that Canberra calls the shots. “I came back and worked on policy planning and then as a private secretary on the staff of the then foreign minister Senator Willesee.

“Seeing the way in which the bureaucracy works to ministers and parliament was a wonderfully instructive experience. “This was curtailed by the fall of the Whitlam government. “I was working in Parliament House in the early afternoon of 11 November when it became apparent that the government had been sacked. “It was one of those experiences you never forget. “Later I was asked to carry out the same role on Andrew Peacock’s staff Interestingly neither he nor Senator Willesee ever asked who I voted for.

“In 1978 I was posted to Portugal which was still caught up in the social upheaval in the aftermath of the 1974 revolution which inter alia had seen an extremely disorderly decolonisation process. “This of course had particular resonance for us because of Portugal’s precipitate retreat from East Timor.

“In October 1978, halfway into my time in Lisbon, I was having lunch one day with a colleague and we were discussing what a difficult time our colleagues in Beirut must be having because of the flareup of the civil war. “On returning to the office there was a telegram cross posting me to Beirut to head the office there! “Life in Beirut could not have been more different. “I arrived in a segregated city in which large parts were no-go areas. There was a curfew and electricity cuts and the central government’s remit sometimes barely extended beyond the gates of the presidential palace.

“Naturally, security was a matter of concern. One lived with the fear that staff might get caught in the wrong place at the wrong time. “I then went to Zimbabwe to join the commonwealth observer group, observing the pre-independence elections which took place in a country raw from the long civil war it had lived through. “This was the election which returned Robert Mugabe as president. “He had been a marxist guerilla, but on the morning the elections results were announced, he made a broadcast and said to all, whites blacks and coloureds, that they were needed and welcome in the new Zimbabwe. “It was an extraordinary speech. If only he had lived up to that promise!”

After Zimbabwe, it was back to Australia for a couple of years working on African and disarmament issues. Then to our mission to the United Nations in New York, where Les worked on a range of issues including decolonisation and Antarctica.

Les was also a member of a security council mission investigating South African incursions into Angola. He returned to Australia where he worked once again for the foreign minister, on this occasion Bill Hayden as head of his office.

“In 1992 I was posted as Consul-General to New Caledonia with responsibility also for French Polynesia. After a stint back in Australia, the position of deputy ambassador in Indonesia was advertised. Les hadn’t worked in Asia, so he applied. A few days before he arrived in Jakarta, the city was in flames and experiencing a mass exodus of expatriates.

“There was speculation at the time that president Suharto’s supporters in the military would intervene to ensure his continuation in office which could have triggered a bloodbath. “Fortunately sanity prevailed and the military stood back as the president was forced to resign.

It was back to Australia in the public affairs division where Les was found himself in charge of the department’s handling of the consular response to the bombing of the World Trade Centre. He was appointed in April 2003 ambassador to the Russian Federation based in Moscow with non resident accreditation to Ukraine, Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Armenia, Georgia, Belarus and Moldova. “I was there for 3 years. Russia is an absolutely fascinating country going through a difficult period of transition from the legacy of the highly regulated soviet system towards a more open pluralistic society.

“On the business front there is enormous potential for Australian business in oil and gas, food and wine, consumer goods and education. “I was actually in Australia in October 2003 when news of the Moscow theatre siege came through. “I hightailed it back as soon as I could. “My colleagues had been in constant touch with the Australian hostage, professor Bobik, throughout the siege but experienced difficulties in finding him after his transfer from the theatre to hospital. “Ultimately we were able to do so and put him in touch with his family which was very satisfying.”

Final thoughts?

“Life’s too short for regrets. “I’m immensely grateful for the opportunity to have served Australia as a diplomat and it’s a career I would recommend highly to students at MHS with a sense of adventure and a wish to work in government.”

What to do in retirement?

“I only retired 2 weeks ago. I’m looking around. There is no private sector equivalent to being an ambassador or diplomat. “You have to determine what your skills are, and try to match them. Perhaps something in a university.